An Atlanta neighborhood tries to withhold ‘a fashion of dwelling’

The telltale signs of gentrification aren’t not easy to area: trusty estate traders procuring for homes, rents hovering, housing costs skyrocketing, longtime residents getting displaced. And they’re all evident in the Grove Park neighborhood of Atlanta, making it allotment of a national sample lengthy mired in lag, class, and never-in-my-backyard insurance policies.

Debra Edelson, executive director of the Grove Park Foundation, describes the system as “white money pushing out Murky individuals.”

Zoning, rent regulate, property-tax breaks, and taxpayer-funded cheap housing occupy lengthy been old to dwelling up progress and sustain neighborhoods diverse. Nonetheless contemporary study reveals the lengthy-time period failure of such tools to temper trade.

Many wonder if, in the end, the wrestle comes appropriate down to how one can disclose a neighborhood. Is it a free assemblage of groups and alliances working to enhance property values, or a selected dwelling with a history that prizes individuals over earnings?

For Cynthia Poe, a Grove Park resident, the utter isn’t gentrification per se. Irrespective of the whole lot, a brand contemporary YMCA has opened, an aged neighborhood theater is being renovated, and further services and stores are all coming.

The level, she says, isn’t to sustain the neighborhood Murky, nonetheless to sustain it culturally intelligent – and to safeguard a communal fireplace.

Atlanta

Cynthia Poe worries about getting squeezed out again.

Initially from Durham, North Carolina, Ms. Poe, a human resource supervisor, watched as a white developer equipped up that city’s historical “Murky Wall Boulevard,” allotment of a gentrification wave that saw lengthy-overdue funding in disadvantaged neighborhoods satirically lead to huge displacement of poorer, largely Murky residents.

She fled her no-longer-familiar neighborhood with its rising taxes late closing twelve months, most sharp to land in the identical relate of affairs in her contemporary dwelling: the majority-Murky, working-class neighborhood of Grove Park in Atlanta. Once a thriving white neighborhood, Grove Park saw white flight in the 1960s. Redlining by banks and diverse monetary institutions little funding as Murky individuals moved in. There aren’t any main grocery retailer chains and no pharmacies. Some homes remain dwelling on dust roads.

Nonetheless passion among white Atlantans is on the rebound. From her hunch, Ms. Poe watches a familiar ritual as trusty estate traders stroll the streets, pointing and procuring for. Debra Edelson, executive director of the Grove Park Foundation, describes the system as “white money pushing out Murky individuals.”

That would maybe maybe as soon as extra encompass Ms. Poe. Rents occupy doubled, and property values are putting homes out of reach of her funds. A newly constructed, three-bedroom dwelling is on the marketplace for $409,000 – in a neighborhood the keep the frequent annual earnings is $23,000. “It goes so rapid,” says Ms. Poe. “And it’s not as if you occur to can lose something. You will lose something.”

The phenomenon of “gentry” stepping into working-class areas isn’t often contemporary. Neither is the displacement triggered by what would maybe maybe be termed the “brew pubification” of a neighborhood. Indeed, extra than a decade after the housing crash of 2008 – and with millions of People now in possibility of shedding their properties attributable to the pandemic – the transformation of Grove Park is allotment of a national sample lengthy mired in lag, class, and never-in-my-backyard insurance policies.

No topic a protracted time of efforts to interrupt this sample, traditional questions remain unanswered: What makes a dwelling a neighborhood? And what does that time period if truth be told mean?

The necessity for solutions is especially dramatic in Atlanta, the keep many residents wear hoodies that reveal “Atlanta influences the whole lot.” Yes, the city helped tip a national election and keep a highlight on racial reckoning. Nonetheless struggles to set up cheap housing and social mobility for Murky residents has the city itself at a demographic tipping level. Predictions level to that in 30 years, the Murky inhabitants of Atlanta would maybe maybe race from lawful over half to most sharp one-third – with white residents making up a third and Asian and Hispanic Atlantans making up the comfort.

Patrik Jonsson/The Christian Science Video show

A decrepit dwelling sits subsequent to a newly constructed one in Atlanta’s Grove Park on Jan. 20, 2021. As the relate has been came right thru by companies and dwelling-flippers, a neighborhood the keep the frequent wage is $23,000 a twelve months now sees contemporary condo costs over $400,000.

“Cities decide to deem extra strategically about the combo of inhabitants, on epic of because the working-class inhabitants is displaced and scattered, you would occupy altering social family, longer commutes – social fragmentation that changes the identification of dwelling,” says Euan Hague, a geographer at DePaul College in Chicago.

Going thru fleet gentrification, Atlanta pushed the dwell button, putting a building moratorium on Grove Park and a whole lot of diverse neighborhoods. Such stoppages are blunt tools that would maybe maybe in the end exacerbate housing complications, provided that the root motive in the assist of skyrocketing costs and rents is a little present. Yet they’d give some breathing room to tackle evolving values that would maybe maybe take care of the respond – and disclose the challenges – to building diverse and intelligent neighborhoods, rooted in history.

A tug of warfare over a “neighborhood fridge”

“When white individuals transfer in, they decide to differentiate themselves, every so generally by renaming total neighborhoods,” says Kathryn Rice, an Atlanta housing activist. “We don’t decide to deem racism in liberal, progressive Atlanta, nonetheless it for sure’s unruffled steady. Town is unruffled very, very segregated. And in gentrifying areas, you’re getting a conflict between what values are there versus contemporary ones, which ends in energy struggles.”

Those struggles play out in slight, nonetheless illuminating ways.

In the gentrifying neighborhood of Pittsburgh, about six miles from Grove Park, a community of residents positioned a “neighborhood fridge” in a city park to assist struggling neighbors in the midst of the pandemic. Nonetheless four households – three white, one Murky – complained. Even though there had been no incidents animated the fridge, the neighbors panicked about crime and the impact on their property values. A pair of days later, the city parks department hauled the fridge away.

For a whole lot of, the wrestle comes appropriate down to how one can disclose a neighborhood. Is it a free assemblage of groups and alliances working to enhance property values, or a selected dwelling with a history that prizes individuals over earnings?

“A neighborhood is a convention of reliance on diverse individuals: who you would borrow money from, who can search your adolescence,” says Kamau Franklin, a Pittsburgh resident. “It’s a neighborhood and a convention. Nonetheless individuals don’t deem it esteem that. They give the impact of being unfortunate individuals who would maybe maybe additionally be disposed of.”

As Atlanta demonstrates, that feeling of being disposable isn’t necessarily hooked as a lot as lag. In this majority-Murky city, those displaced and those with the authority to assist them are usually the identical lag.

No topic when it comes to 50 years of Murky leadership, the city has fallen a long way short of promises to substitute thousands of razed public housing objects with cheap housing. Lack of economic mobility for poorer Murky residents is extra pronounced in Atlanta than nearly anyplace else in the U.S., with the median household earnings of white families nearly three situations that of Murky families.

That scenario, not lower than in allotment, is the of Murky mayors taking a judge forward extra than taking a judge assist, says Ms. Edelson of the Grove Park Foundation.

Ron Daniels, founder and president of the Institute of the Murky World 21st Century, has urged cities esteem Atlanta to gape the impact of gentrification as an existential and instantaneous possibility to Murky tradition.

“Many of these mayors weren’t outfitted to tackle the phenomena of gentrification and would maybe maybe even be complicit,” says Mr. Daniels, who convened a 2019 Nationwide Emergency Summit on Gentrification. “Whenever you occur to originate sure forms of fashion without belief the persona of market forces, then you definately are contributing to the displacement of Murky individuals and tradition without being aware about it. And a few would maybe maybe be aware about it.”

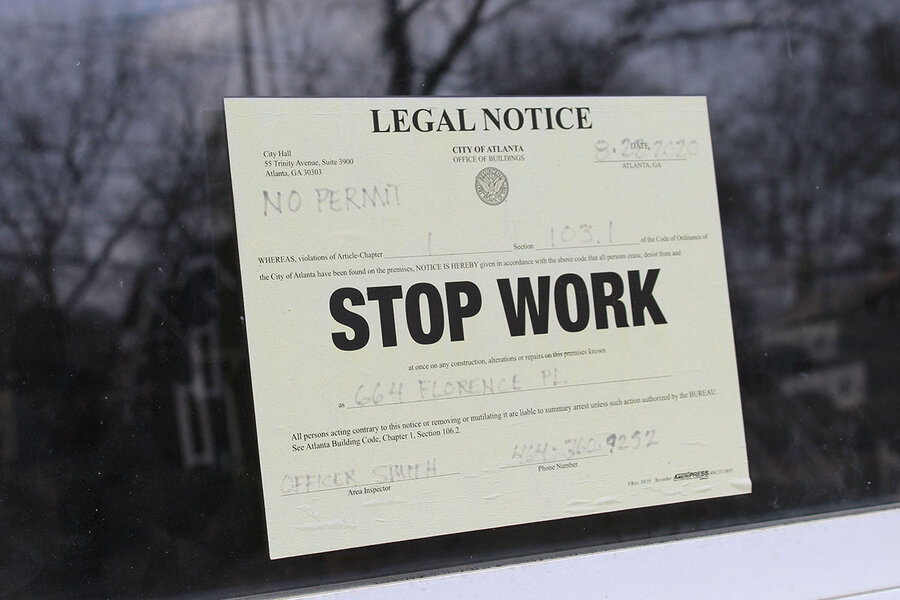

Patrik Jonsson/The Christian Science Video show

A city-issued dwell work order is viewed on a condo in Grove Park on Jan. 20, 2021. The historical Murky working-class neighborhood remains beneath a city building moratorium to stem fleet gentrification that threatens to displace Murky workers and dramatically shift Atlanta’s demographics.

Balancing progress and “a fashion of dwelling”

After the city invested tens of millions in a brand contemporary park-and-breeze machine shut to Grove Park, Microsoft announced closing month the acquisition of a huge parcel in the midst of the neighborhood for a brand contemporary corporate campus.

To make sure, Microsoft President Brad Smith has vowed not most sharp to rent from Atlanta’s Murky educated class, nonetheless also to work to sustain the neighborhood diverse. The problem, says Ms. Edelson, is that the race of trade will profoundly reorder the neighborhood lengthy earlier than Microsoft opens its doorways.

Nonetheless there are signs of progress. About a decade previously, a collaborative effort succeeded in revitalizing East Lake, a neighborhood on the choice aspect of the city. The nonprofit Reason Built Communities, which makes cheap housing a top priority for redevelopment, grew out of that effort and now supports revitalization not most sharp in Atlanta nonetheless around the nation.

In the closing three years, Atlanta has added 5,600 cheap housing objects, and the mayor at the moment signed an executive order investing $50 million in bond funding for affordable housing.

Efforts that diverse cities are exploring would maybe maybe assist Atlanta as successfully – corresponding to insurance policies that dwelling aside a share of tax revenues from rising property values to be reinvested as low-earnings housing. Addressing not-in-my-backyard insurance policies that restrict cheap multifamily housing would maybe maybe assist too.

“It would maybe maybe be diverse if it was more straightforward to earn in every single dwelling, the keep every neighborhood is altering at a late price – so as a substitute of a firehose on this one relate, your total city will get a gentle watering,” says Evan Mast, an urban economist on the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Review, a nonpartisan group in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

For now, Ms. Edelson calls Grove Park a “gargantuan social experiment.” Nonetheless “every person need to be rowing in the identical route, otherwise we lawful earn urge over,” she says.

The problem for Ms. Poe and others isn’t gentrification per se. Irrespective of the whole lot, Grove Park saw the opening of a brand contemporary YMCA, an aged neighborhood theater is being renovated, and further services and stores are all coming.

The level, she says, isn’t to sustain the neighborhood Murky, nonetheless to sustain it culturally intelligent – and to safeguard a communal fireplace.

Nonetheless and not using a general legend about what it skill to be a neighborhood – and the sense of belonging that incorporates it – improvements would maybe maybe be non permanent, she fears.

“Yes, individuals will come, nonetheless and not using a fashion of dwelling, they’ll depart lawful as rapid.”